- Public Opinion and Political Participation in Authoritarian Regimes

- From Giving Blood to Getting Vaccinated: Exploring Voluntary Compliance

- Everyday Governance in (Post-)Communist Contexts

Public Opinion and Political Participation in Authoritarian Regimes

My academic path began with an interest in why many Chinese express strong trust in central authorities but comparatively weak trust in local governments. Investigating this trust differential has sparked my subsequent research on public opinion and political participation in authoritarian regimes.

In an article published in Asian Survey, I analyzed public preference for strongman rule. After Mao Zedong’s time in power, the Chinese Communist Party emphasized institutionalizing collective leadership and warned against cults of personality. Over the past decade, however, a strongman has risen to power. Against this backdrop, I assessed the extent to which the Chinese people prefer a political system characterized by a leader with unchecked power. This assessment also contributes to a broader understanding of political strongmen and their popular bases worldwide.

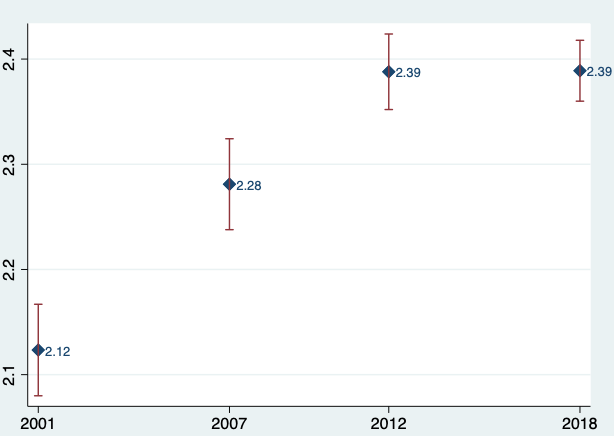

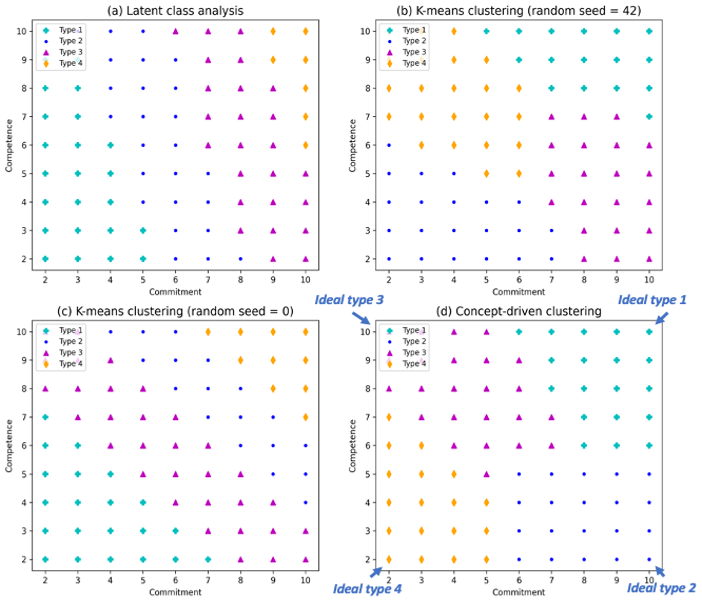

More recently, I examined the effects of political trust on political activism by adopting a concept-driven clustering method. The idea originated from an attempt to label survey respondents into different attitudinal types to build a training set for supervised learning. This made me wonder: Instead of training the algorithm to learn from empirical observations, could it be trained to learn from a priori theoretical conceptualization? In pursuit of this idea, I drew on the intersection of constrained programming and machine learning/data mining, proposing a clustering method that constrains the learning process using ideal types of each attitudinal type.

In an article published in The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, I applied this concept-driven clustering method to analyze data from thirteen nondemocracies. Specifically, I leveraged domain knowledge about trust in commitment and trust in competence to develop a fourfold typology of political trust. The ideal types of each trust type were then used as initial centroids for k-means clustering. By guiding the clustering process with these ideal types, this method ensures that survey respondents are categorized into the four conceptually derived trust types, setting it apart from data-driven methods (see supplementary materials for an illustration).

Results reveal that in nondemocracies, political activism is not limited to individuals with low trust in government; those who trust the government’s commitment but doubt its competence are also more likely to engage in activism. Substantively, this study refines scholarly knowledge of political trust and its effects on political activism. Methodologically, it introduces a new way of grounding social science research in well-established theories and concepts.

From Giving Blood to Getting Vaccinated: Exploring Voluntary Compliance

Another focus of my research is voluntary compliance. Modern societies depend on individuals making essential contributions to function, such as paying taxes, getting vaccinated, and giving blood. Although the voluntary provision of such contributions is widely regarded as desirable, it often falls short of meeting societal needs. This raises a series of important questions: Why is voluntary compliance considered desirable? Under what conditions is it enabled or hindered? What measures are adopted when voluntary efforts fall short? How can these measures be categorized, and how effective are they?

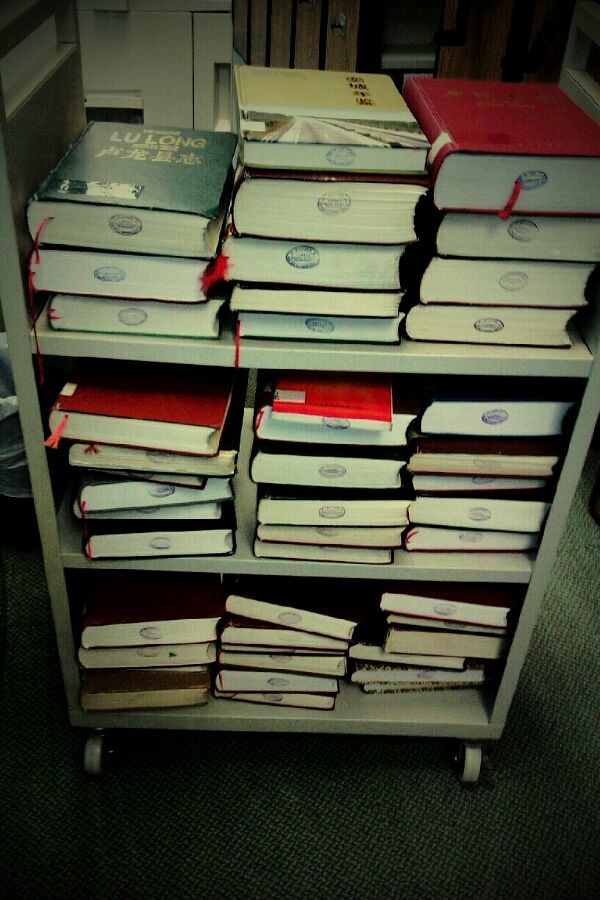

I first explored these issues through a study of blood collection in China. In an article published in Modern China, I relied on documentary sources, particularly local gazetteers (difang zhi), health gazetteers (weisheng zhi), and health annual chronicles (weisheng nianjian), to revisit the blood-borne HIV epidemic that claimed tens of thousands of lives in the 1990s—a catastrophe widely attributed to the market-oriented approach to blood collection.

In response to the catastrophe, the Chinese government promoted voluntary blood donation. This improved safety but also created new challenges for maintaining an adequate supply. In an article published in The China Quarterly, I combined fieldwork and survey data to examine why Chinese citizens are reluctant to give blood voluntarily and how the government mobilizes captive donors through work units to secure public health needs.

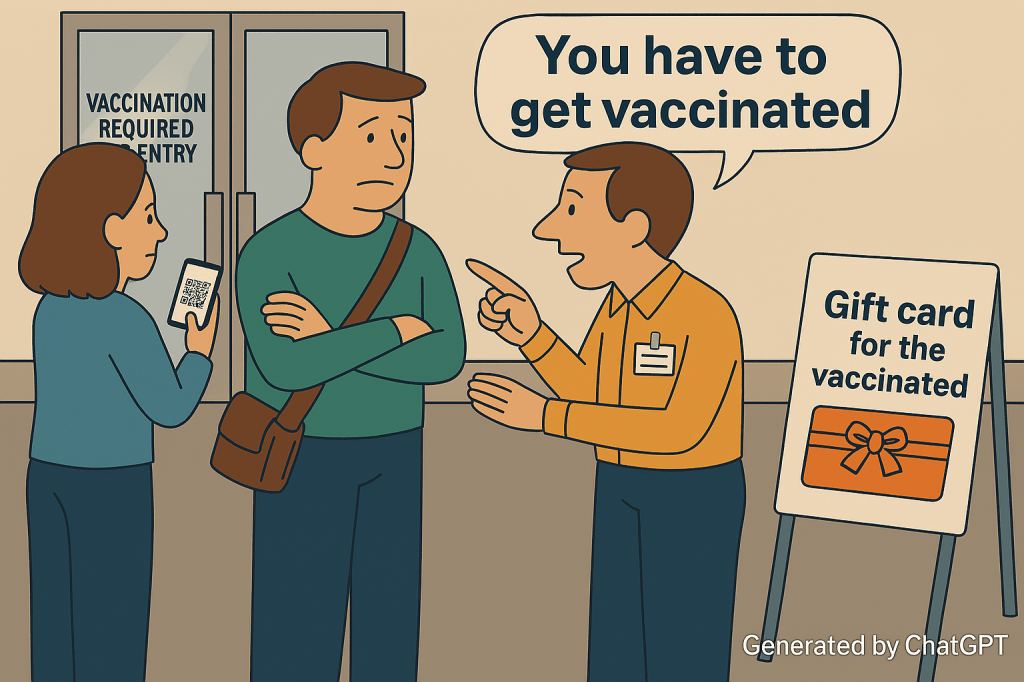

While working on blood collection, I also extended the discussion of voluntary compliance to other contexts, including vaccine uptake, though at that time, I could not have foreseen how pressing vaccine uptake would become in just a few years. In a recent article published in Global Public Health, I reviewed how governments in China and elsewhere adopted coercive measures to motivate vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. To evaluate the effectiveness of these measures, I designed a survey question that asked not only whether respondents were vaccinated but also why they chose to do so. This design made it possible to identify individuals who were motivated by coercive measures, thereby assessing their prevalence within the population and determining which subpopulations were most likely to be influenced. Given the controversy surrounding such measures, this enhanced understanding of their effectiveness could help formulate targeted policies to combat infectious diseases and safeguard public health.

Everyday Governance in (Post-)Communist Contexts

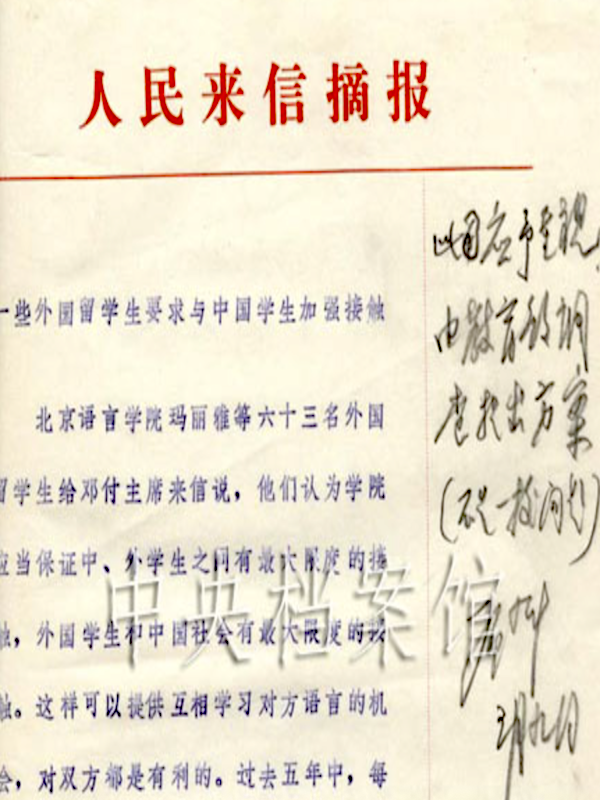

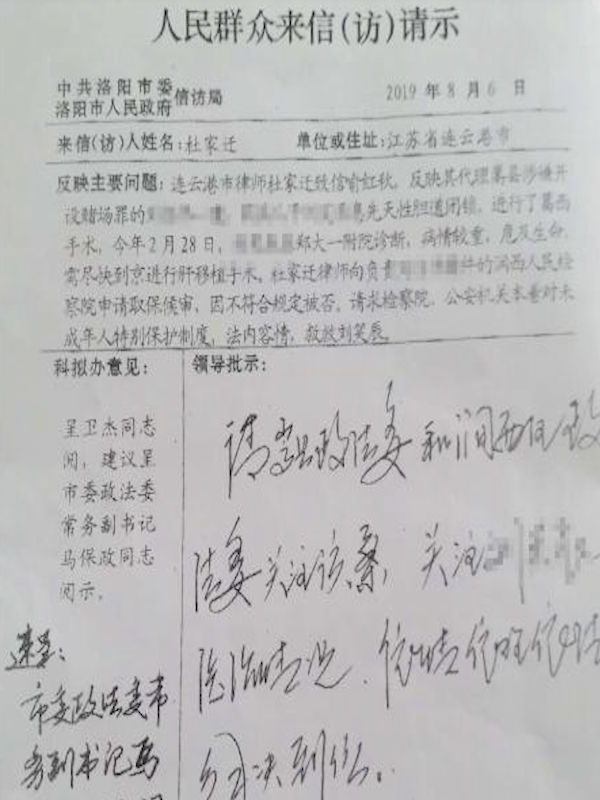

I was a participant in the European Research Council-funded project “The Microfoundations of Authoritarian Responsiveness: E-Participation, Social Unrest, and Public Policy in China,” led by Christian Göbel. This project built a database containing tens of millions of cases that documented citizens’ reports of everyday issues and the government’s responses. Within the project, I specifically analyzed how local Party and government heads, who wield substantive power in the Chinese political process, responded to such input, using their written instructions (pishi) as an indicator.

In an article published in Problems of Post-Communism, we reported that local Party and government heads focused on only a small subset of the citizen input they received. Using supervised machine learning techniques for text classification, we further showed that while citizens raised numerous concerns about public services, political leaders placed greater emphasis on policy areas such as bureaucratic malfeasance, social welfare, labor affairs, environmental protection, and business affairs. Moreover, they paid more attention to citizen complaints and suggestions than to inquiries. These findings shed light on the types of input that Chinese leaders prioritize when faced with information overload from participatory institutions.

In a research note published in China Information, we conducted a close reading of leaders’ written instructions from a data-rich county. We found that, in addition to responding to hard-to-obtain information, local Party and government heads occasionally addressed long-standing issues of which they were already aware, primarily to demonstrate concern rather than to pursue substantive solutions. They also tended to give instructions on issues aligned with the current core work agenda (zhongxin gongzuo) to support its implementation, as well as on issues involving multiple government agencies to prevent buck passing. These findings offer insight into mechanisms of government responsiveness that are often overlooked by quantitative approaches.

This project on government responsiveness in China also prompted me to explore parallels with practices in the Soviet Union and East Germany, leading to a broader interest in how communist regimes collect information and manage society in everyday life.